It’s been cold the last few days in Rio. It even rained. In fact, it rained a lot. Today the sun returned to the sunny shores of the marvellous city. Today I had plans to get up and go to the beach to draft this post.

Plans changed, though.

At seven am this morning, I woke up to the sound of fireworks. They do like to throw a party here in the continent’s largest favela, but this wasn’t a party. For a start, it was seven am.

Within thirty, forty minutes, the fireworks began to fade and the sound of bullets began to pierce the crisp, morning air. As I’ve mentioned in previous posts, bullets in a favela are the norm. No one bats an eyelid. In the words of the secretary for public security here in Rio, “a bullet in the favela is one thing, a bullet in Copacabana is another”.

This, however, wasn’t just a bullet. When you can still hear bullets at 10am – three hours after you heard the first one – you know something isn’t right, you know this is more than just the odd bullet.

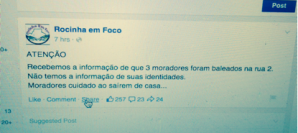

So, I turned on my computer. The trusty community Facebook page, Rocinha em Foco, will surely be able to fill me in on what’s happening?

“Intense gunfire in various locations across the favela”, “Do not leave your house, the police are carrying out an operation”, “Intense gunfire on street 2, street 4, Cachopa and Ropa Suja”

So, intense gunfire everywhere then. Watching movies, reading the news, studying the impact of police interventions in favelas and even spending seven months living in favela had given me – at least I thought – a pretty good idea of what it’s like to live in a favela in the face of such confrontation. I was wrong.

To hear the sound of rifle fire and grenades at the end of your street is different. To have to explain to your friend on Skype that you can no longer continue your conversation because your head is so confused is different. To get word that the side of your friends house is covered in bullets and a young boy suspected of being involved in the traffic has been murdered because he wouldn’t cooperate with police is different. Everything about this day was different.

Today I was introduced, first hand, to the realities of state intervention in favelas.

Probably the most shocking thing – aside from the three hours of gunfire, bomb echoes that felt like they were coming through my bedroom wall, and strangely empty streets – about the whole incident was the look on one man’s face as he hung out of his window and gestured towards me. The man is around sixty years old. He is the kindest, friendliest and most approachable person I think I’ve ever come across. Yet, as bullets battered the morning air, my old aged neighbour could do nothing but smile and laugh as he hung from the window of the house he built.

This man had internalised his community’s violence long ago. Locked it up and thrown away the key so the violent reality of the divided city he lives in could no longer get in the way of his day. Fair play to him. Fair play to the hundreds of thousands more people like him across the city who have done the same.

I was later told by another friend that peoples’ bosses are getting annoyed because the many residents of Rocinha were arriving to work late or not arriving. I mean, what a joke! How dare they not pass through the crossfire to ensure a punctual arrival at work – the bloody cheek! I’m sure there are many bosses without this attitude, the fact that some do have this attitude is, nevertheless, disheartening.

The Government set out with an ambitious target of re-taking areas previously controlled by drug gangs in time for the World Cup and upcoming Rio 2016 Olympic Games. They called it “Pacification”. They promised a more inclusive city. They pledged social and public services, tranquillity and peace.

Instead, they’ve brought bullets, bombs and created angry bosses.